‘Hey Doc: I’d love to talk’: When athletes work on their mental game

By: Megan Ryan, Star Tribune

Kyle Gibson was 29 years old, had an 8.20 ERA and was back in Pawtucket, R.I.

Five years into his major league career without a breakout season — and only one with an ERA below 4.00 — and the Twins pitcher found himself yet again with the Class AAA Rochester Red Wings.

In his first six starts of the 2017 season with the Twins, he hadn’t lasted six innings or given up fewer than three runs despite having switched up and improved his workout plan and throwing angle.

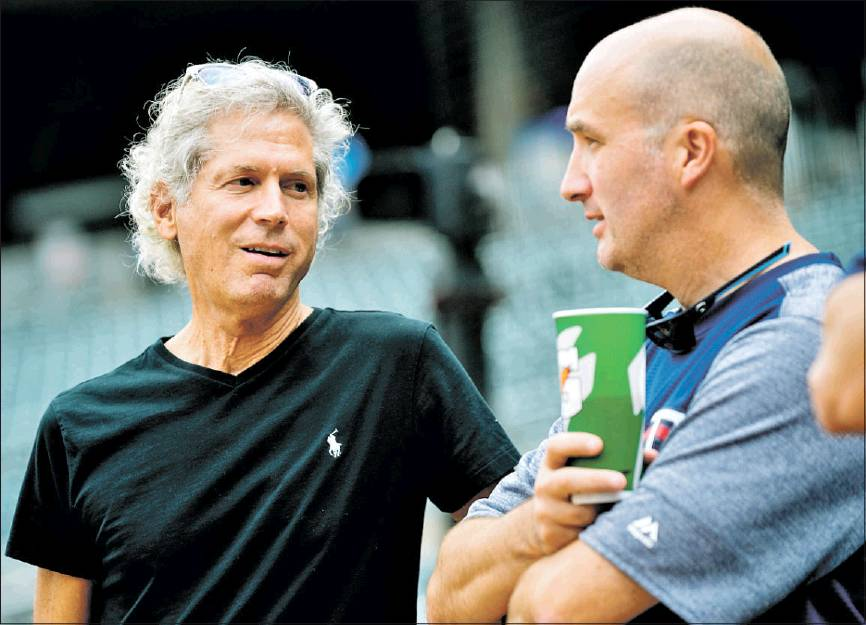

On the field at McCoy Stadium that May day, Gibson caught sight of a familiar shock of white hair. It was Rick Aberman, who holds a Ph.D. in developmental psychology and family therapy and has about 30 years of experience. A common sight at Twins batting practice at Target Field, Aberman — who has worked with the club since the early 1990s — happened to be making his once-a-month visit with the Red Wings.

“Hey, Doc, I’d love to talk to you a little bit,” Gibson said. The next day, the two sat in the dugout ahead of batting practice, and Aberman quickly pinpointed Gibson’s troubles.

“He was hitting the nail on the head. Everything he saw,” Gibson said. “He was like, ‘Listen, I can see you carrying the struggles. I can see it in your face. I can see it in your demeanor.’”

Aberman’s official job with the Twins as peak performance director, which he’s held for 10 seasons, speaks to the burgeoning role of psychotherapy in helping athletes navigate the mental side of performance and achieve a competitive edge. The field first gained prominence in the U.S. about 50 years ago, but the Twins are the only team of the Twin Cities’ six major professional sports franchises to officially have a sports psychotherapist on staff.

Aberman said his job is to “see things differently,” and he does a lot of watching and making himself easily accessible to players.

“Most of the people I see are pretty successful at what they do,” he said. “They know how to catch. They know how to throw. They know how to hit. … But I’m always wondering, ‘OK, so what’s going on in their life that’s getting in the way?’ ”

For Aberman, it was clear Gibson’s internal monologue while on the mound was a little something like this: “OK. First and second. I need to get a ground ball right here.” And when he didn’t: “I’m a failure.”

“I was putting so much pressure on myself with each pitch,” Gibson said. “And it just, it was starting to weigh on me.”

THE FIELD

When Eastern European countries dominated the Olympics in the 1970s, part of the reason for their success — minus the doping — was focusing on helping athletes understand their minds. So competitors in individual Olympic sports and hockey, from which many Eastern European players came to the U.S., were some of the early adopters.

Charlie Maher, sports psychologist and director of psychological services for the Cleveland Indians, is one of the more well-known names in the field and first started working with athletes 30 years ago. While he’s done most of his work in baseball, he has also worked with several hockey teams, including the Wild in the 2000s.

Maher said what makes hockey and baseball especially suited for accepting sports psychology is the culture of development from the minor league systems.

It’s part of Major League Baseball’s most recent collective bargaining agreement, the only one of the six major U.S. leagues to include it: “Each Club shall provide Players with access, on a voluntary basis, to confidential sports psychology resources in a private space.”

A spokesman from the Vikings said the team has contracted with a consultant for several years. Spokespeople for the other Minnesota teams said they do not regularly use sports psychology services.

THE SPECTRUM

On one end of the sports psychology continuum are what people typically think of: the mental skills aspects, like on-field focus. In the middle, there are life skills: everything from nutrition to substance use. And on the other end is behavioral health, such as psychological conditions of anxiety or depression. Techniques vary as well, from therapy to visualization to heart rate variability training.

“When people hear sports psychology, they think, like, you’re going to lay on a couch and talk about your feelings,” said Nick Rallis, a former Gophers linebacker. “But for me, it was psychological training, just another component of preparation for competition.”

Wild defenseman Matt Dumba said his junior Western Hockey League team, the Red Deer Rebels, brought in sports psychologist Derek Robinson. And from working with Robinson from age 16 to when he joined the Wild in 2013, Dumba learned strategies he still benefits from as a pro.

“You don’t want to be too high or too low. You really can’t let one play define your game, your season, how you’re playing, how you’re feeling,” Dumba said. “It’s not about that, and you’ve just got to trust the process, that what you’ve been doing is the right things, and believe in that.”

“He’s a great dude,” Dumba said of Robinson. “He worked with all the guys and whenever you wanted to work with him or use him. I ended up using him lots and developing visualizations before the game and what my kind of set routine was. And I’ve kind of used that ever since.”

Christian Horn first worked with mental skills coach Hans C. Skulstad of the Center for Sports and the Mind in Golden Valley. Horn, the captain of Benilde-St. Margaret’s hockey team, began with Skulstad after teammate Jack Jablonski endured a paralyzing spinal cord injury in a December 2011 game. Horn returned a few years later when re-evaluating his hockey career in the midst of transferring from the Gophers program and has continued as he pursues an NHL career.

“Hans has turned my life around, not just in my sport but at home, relationships I have with my parents, my sister, everyone at my house and my family,” Horn said. “I’ve become a better human being.”

More athletes embrace sports psychology now, but it’s been a slow acceptance.

“Initially, there was a lot of reluctance,” Maher said. “It was perceived many times by coaches and players, athletes, as something negative, meaning you have a problem, you’re screwed up, you cannot do well and you need somebody to help. There’s still that element of a problem, and particularly in men’s sports where there’s that macho attitude.”

Maher said many athletes are coming to see it as just another support service, like strength and conditioning or athletic training: a way, Maher said, to take “athletes who are doing very well and make them better.”

THE RESULTS

For Gibson, the change came with a simple mind-set shift, moving baseball from a “need” to a “want.”

It took some time for that mentality to manifest on the field. Gibson did a second stint in the minors in July, but his turnaround eventually helped the Twins reach the playoffs. The Twins won Gibson’s last eight starts of the season, and Gibson finished with a 12-10 record, dropping his ERA to 5.07.

“I was slowly over the last year and a half … losing confidence and losing the identity in myself as who I was as a pitcher, and it took a little bit to get that back,” Gibson said. “I’ve kind of felt the mentality-wise that Dr. Aberman talked about has really kind of sunk in and given me some more confidence and allowed me to look at who I am as a pitcher with a better lens and realize that one outing doesn’t determine whether I’m a good pitcher.

“He had seen how I was reacting to certain things and saw my body language, and he probably knew what he needed to tell me,” Gibson said. “It just so happened that that was exactly what I needed to hear.”